rhythm vs notation | 2025-12-12

this week's topic: rhythm vs notation

where do the concepts of technical proficiency and musicality meet?

what divides a real musician from a pretender or a robot?

anything?

can someone be a musician without some level of technical proficiency?

isn't beauty in the eye of the beholder and, therefore, any musician real if they have an appreciative audience?

i've been in heated debates on some of these questions and, at other times, been shocked by the visceral reactions of people to concepts like "really knowing music" and "real musicians".

who says? who gets to determine what is excellent and what is not?

how does one cross a line from learning to real knowledge in music?

if i love Bach and you love Skrillex, which of us really understands what makes music good? (it's obviously me...)

they played different things...

there are a few conflicting truths here.

the first is that there needs to be some agreement on a very broad scope as to what music is and how it is perceived.

the second is that, to be understood, music needs to be relayed from one musician to another over time and space.

the third is that music is meant to be intuited and felt as much as it is to be accurately reproduced.

i'm making a lot of assumptions in those statements, but i'll probably get to those later... probably.

to start, there needs to be some agreement on what constitutes music as a concept and experience. there are a host of different interpretations for this. western music has some very broad answers; eastern music does as well and they are very different. each ancient culture has slowly built its own set of assumptions and rules determining proper music. we can dig deeper and deeper to find near infinite specificity in genre and locale. check out this fun webpage that attempts to catalogue all musical genres: EveryNoiseAtOnce

for the purpose of this article, i will pick western music as a broad agreement for musical understanding. this makes sense because i know it better than any other musical tradition.

carrying on with our initial conflict, how do we transfer music from one composer or performer to another over time and space. how much of the performance can be written down, codified, notated, and distributed without losing the very essence of the sound and intent?

today, i can create a song on my computer, send around digital files of my performance for anyone to hear, and i could, should i be so skilled, create the musical notation to accompany it. or, if not musical notation, hints toward the correct voicing, chord structure, lyrics, timing, etc. Skrillex can do this, too.

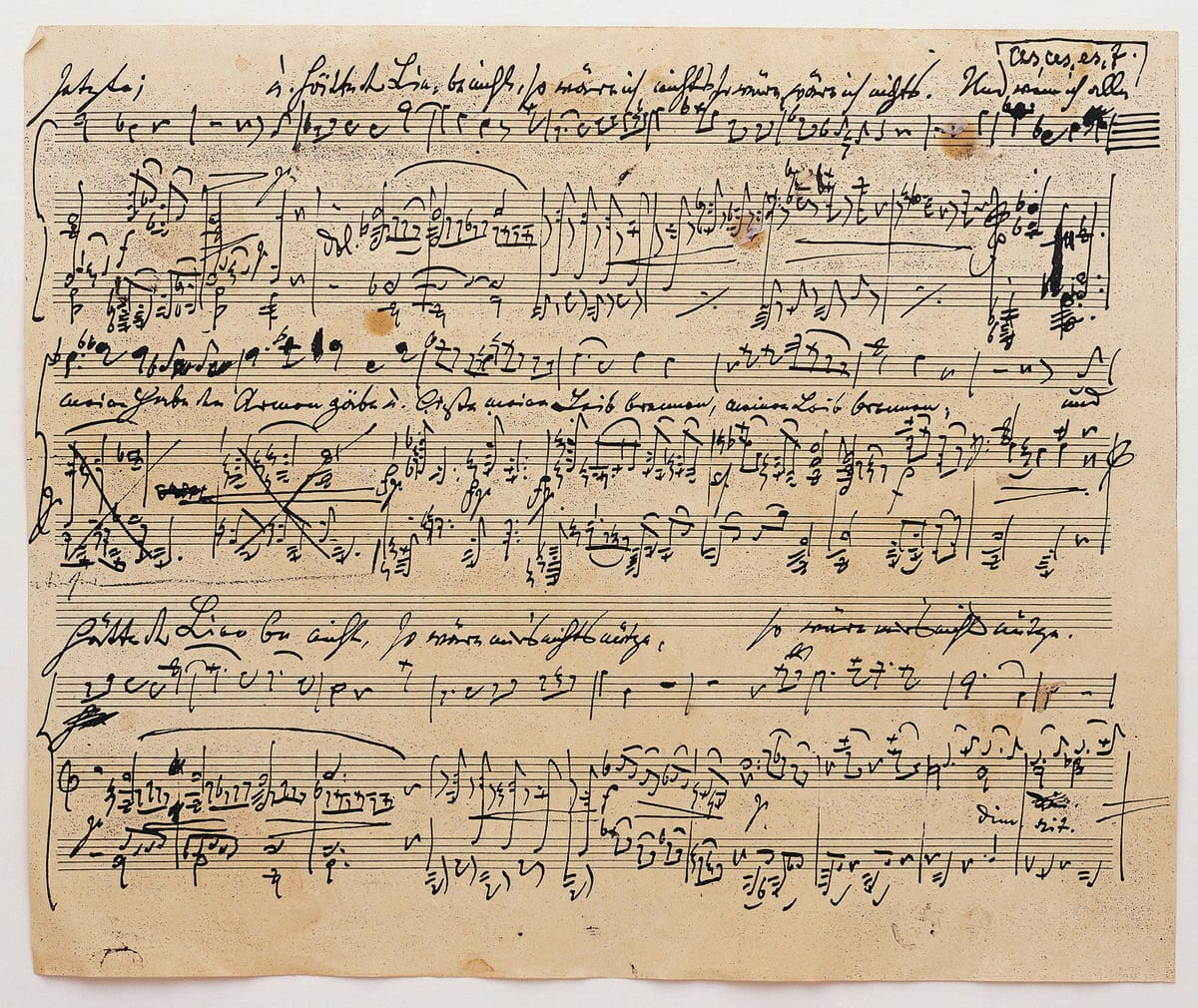

in the 17th century, Bach could only produce his music in two ways: performance and sheet music (read: musical notation).

the performance, while thrilling, was a snapshot. it was timeless, eternal, and fleeting all at once. you would never forget it, but you would never hear it again. there was no bootleg or official live session recording. there was no recording at all. but it was still a production of music; a display of talent and art.

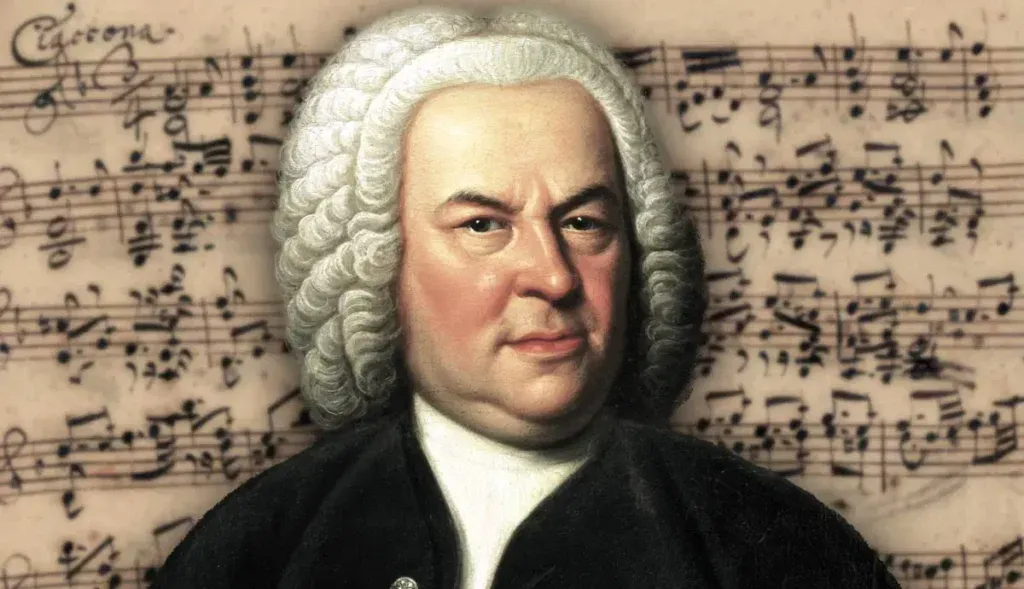

but i know who Bach was as well as i know who Mozart, Palestrina, John Denver, The Bee Gees, and Skrillex were. i know some of Bach's music by heart, having heard it so many times on recordings and in live performance (not by Bach himself).

cultural familiarity with Bach is not exclusively due to excellence in historic study and demography but also to the continued recognition of his brilliance in the history of music (western or otherwise).

and, as i labour to get to the point here, we don't just agree theoretically that there was someone named Bach and he was good at music. we can judge for ourselves because we can perform his music as produced on sheets of paper and reproduced generation after generation.

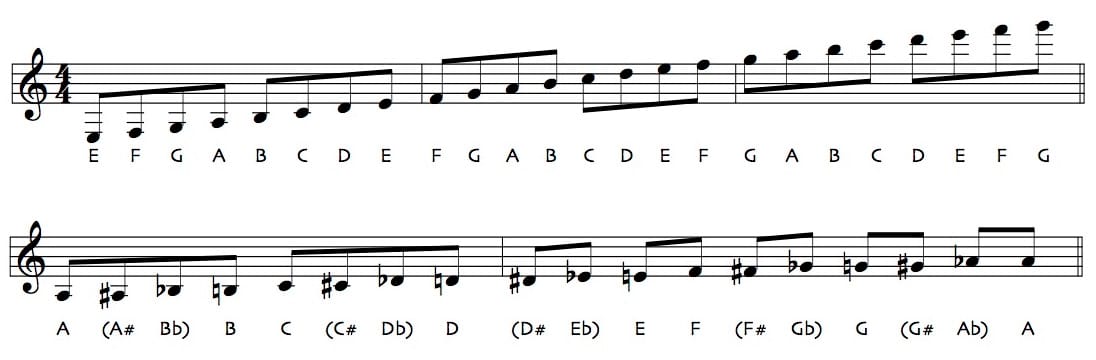

now we've reached part of the agreement in western music that i was mentioning above: since we've agreed on what music is, we need a way to codify it that everyone agrees upon. we need a language that can be taught and understood by those willing to teach and to learn. thus, we have western musical notation.

i could go on and on about the why and how concerning these notes, the reasons for using these letters and only seven letters that (unless you're old school german and use eight), and many other things i find fascinating about the theory behind this.

but i won't... much.

the very short story is that it all relates back to a keyboard and fits within the constraints of what we would know today as a piano.

the reason i'm bringing this up at all is because it falls at the heart of the initial questions of where the line is between a 'real' musician and a student or a pretender.

musical notation is a way to ensure music is reproducible, understandable, and portable over time and space. without it, the skill of Bach and many similar geniuses would be lost to obscurity.

but what is it doing? it is attempting to reproduce a sound, a performance, an experience in a rigid and rigorous manner: these lines mean these notes, this symbol means higher notes, these numbers mean this many notes fill a measure, and so on.

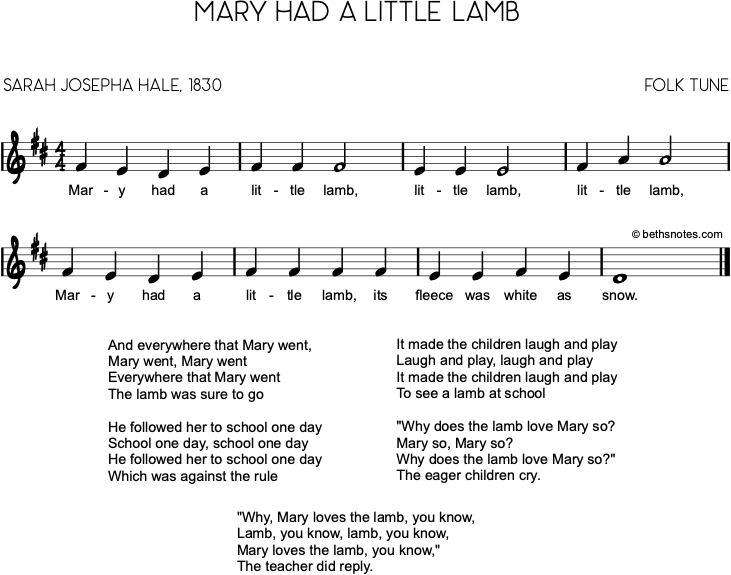

using this system, it is certainly possible to relay a lot of information about the intended sound. if we know how fast, how long, and how high or low notes should be, we get a long way into being able to reproduce it. even with this small amount of information, we can send around a sheet of simple music and have people playing Mary Had A Little Lamb's melody across the world.

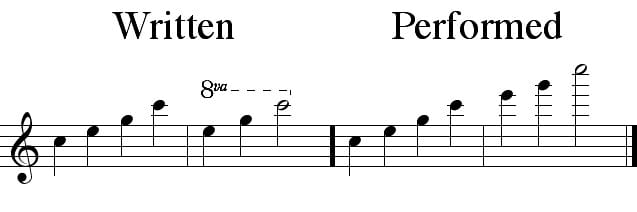

notation gets significantly more complex as it attempts to convey feeling and emotion. there are simpler concepts like phrasing and dynamic or rhythmic changes that help a performer grasp the intent of the composer.

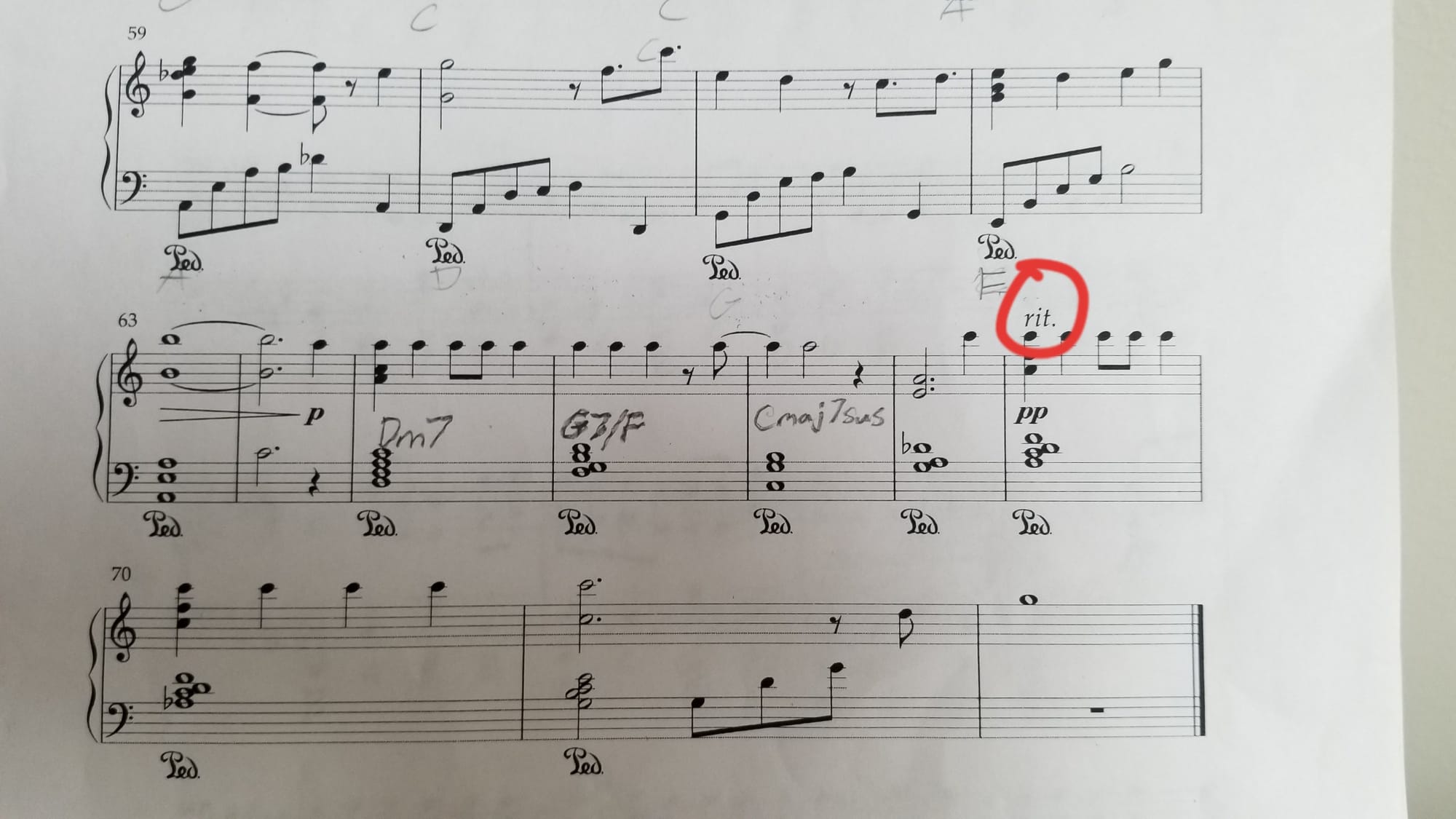

if you want to portray a trill, you skip writing a billion notes and can add the following instead:

if a western musician wants to add some eastern or middle eastern flare to a composition, things get a lot more tricky. western music notation doesn't have a symbol or agreed upon notation for micro-tonal vocalizations or instrumentation. there are only so many notes. if it can't be played on a piano, it can't really exist in western music. or, at least, you can't write it down.

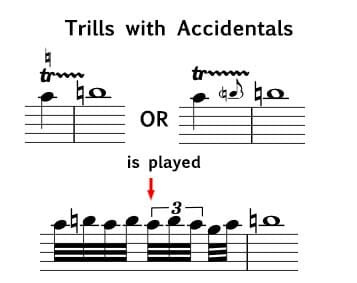

what if you want to convey more complex changes in a piece? a little rhythmic pull here. a sudden hush there. it's possible to do this with notation, but now you're getting into a space where interpretation of notation takes over. a concept like sforzando, which translates from italian more or less as 'suddenly strong', is a push in the right direction but it can't tell you what 'suddenly' means or what 'strong' means. how suddenly? how strong? in comparison to what? the performer needs to choose. the performer decides.

in fact, for every bit of musical notation, each and every jot and tittle, the performer decides. how many concerts have you sat through and mumbled to the person beside you "ugh, this is way too slow" or "this is too high for that singer"? there is an infinity of interpretation in every musical score. you don't have to play it at the written speed. you don't have to play it in the written key. in fact, you don't have to play any of it as written but you will, at some point, no longer be producing the music intended by the sheet music.

so we find ourselves now a little closer to defining a line where 'real' musicianship exists,

in the totally free license to interpret notation as one sees fit, a performer must choose a level of constraint on their freedom. if i want to play Bach's music, i need to choose to play the written notes accurately and in time or it will not sound like it should. i can, however, choose to play some parts more quickly and some more slowly, leave a longer gap in some place, play a section louder or softer, all in an effort to convey not just the music on the page but the emotion it suggests.

and that's where the line is: the ability to elicit emotion through performance.

it is said that music is the language of the soul.

great musicians know this either intellectually or intuitively. how they employ that knowledge or that sense varies widely.

Bach used all sorts of musical tricks to convey hidden meaning or to match a lyric with sound, not just because tricks are fun but because they can add something to a musical experience beyond notes and rhythms. he wrote his name into music with the Bach motif, some say to acknowledge his own need of salvation. he expertly employed word painting (hear the majesty of the Father, the sacrifice of the Son, and the Spirit descending upon you in his Magnificat) to convey meaning through sound along with words. These tricks are reproducible in musical notation, but suggest that the music is not entirely on the page but somewhere else. Bach plays within the rules of musical notation but works through them to create something greater; to move the soul with sound.

other artists toy with musical rules to convey meaning in clever or silly ways. Radiohead uses a rhythmic pattern (if you break it into eighth notes) of 3-3-4-3-3 as the basis for 'pyramid song', writing a rhythmic pyramid directly into the song, thus letting the notation, in part, guide the creation of the song itself. while this is weird, it also helps serve the unnerving and otherworldly space of the song.

lalo schifrin took inspiration from morse code to create the mission impossible theme song (m = long long; i = short short), creating an iconic sound and adding some sneaky spy stuff back into his music.

countless modern artists seem to rage against the constraints of music theory by rapidly switching time signatures or keys as if to prove that they cannot be held back. poly-rhythmic tomfoolery is all the rage.

all monkeying and trickery included, we're still deeply within the bounds of western music theory. you can math out a poly-rhythm and accurately note it down.

but what of musical genres that don't really fit, or don't seem to. what about jazz, where the notation is often just a suggestion to get you started in the right place and then a free flow of musical talent beyond that. what about deep southern blues, where you can certainly write it down word for word and note for note but if you did you'd have missed the point entirely.

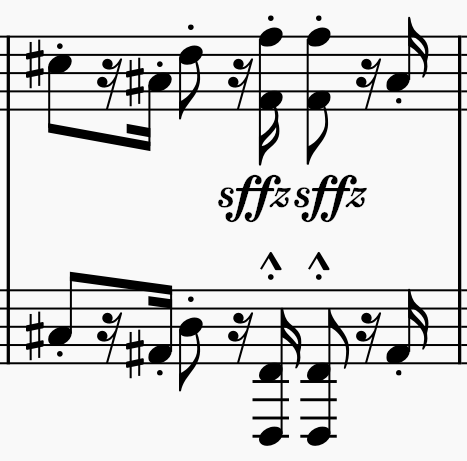

and what about Skrillex? i'm sure i could write down a crisp notation of his music, with thousands of ledger lines or 8va's to account for the pulse stealing ultra-bass and mind-rending electronica of his dubstep creations, but what would i be missing?

could i note down which waveforms he was using for this or that sound? would i write down the specific synthesizers? if i did, could someone reproduce it? and, what's more, do his live performances even sound like his records? would codifying his music be meaningful at all if his music is almost exclusively about the experience and the soul-speaking instead of the rules?

this brings us to the third conflicting truth: that music is meant to be intuited and felt as much as it is to be accurately reproduced.

Skrillex creates a vibe and a scene. you can feel the beat and dance and the lyrics don't really matter. Bach, likely, was also creating a vibe, although his was less about dancing and more about staid germanic praise. deep southern blues and jazz are about the feel and so are genres like jam rock or edm. someone familiar with the genre can intuit how to reproduce the music just by its very nature, and some technical skill.

is that where the line is, then? being able to 'really know' how to reproduce or even to create a sound that fits beautifully into a genre?

if my choir becomes the world's foremost experts on Josquin and have his entire repertoire committed to memory, that probably makes us a 'real' choir and probably means we 'really know' Josquin, but that's pretty limited. what else do we know? we can probably reproduce a wide array of choral music if we've mastered Josquin, but can we branch out into other things? would being able to do so be more meaningful?

if i study guitar long enough and master it, being able to seamlessly flow into rock, pop, classical, metal, folk, and any other genre, have i made it to 'real'? if i can hear a song on the radio and immediately reproduce it on my guitar, am i good?

if i can hear a song in the chapel, go home, and write it all down on sheet music, do i have a gift?

when my nephew was born, we knew he had rhythm. it was part of who he was. he just felt it. that is a gift, too. did that gift mean that he could accurately reproduce the appropriate drum beats as written in a score? well no, but he sure could thump his feet to whatever we were listening to, right on beat.

it's that sense of the music, the feel of it, that separates good from great, whether naturally gifted or not.

technical mastery of an instrument isn't beautiful, though it may be functional. understanding the technique required of a particular genre has a certain artistry but doesn't teach you how or when to employ it. memorizing the score of an oratorio is an impressive feat but doesn't mean you can sing it or play it or even that you understand it.

truly impressive musicians, the ones who 'really know', are certainly technically proficient but they also have an interpretive intuition that allows them to turn notes into rhythms, structure into feeling.

the conflicting truths of broad agreement in musical understanding, musical reproduction, and how we can elicit emotion with music only matter when they are seen as helpful tools. they aren't the answers or even the questions.

real musicians might understand a lot about western music (or eastern or whatever) and they may be fluent in musical notation, and they even might eschew all of that to just feel the groove, but what sets them apart is their gift of translation: interpreting for us all the language of the soul.

so far on rhythm vs notation